Wichtige Punkte

- Altersregression ist eine mentale oder emotionale Rückkehr in einen jüngeren Zustand, die oft durch Stress, Trauma oder emotionale Überlastung ausgelöst wird.

- Es kann freiwillig (absichtlich in der Therapie eingesetzt) oder unfreiwillig (ein unterbewusster Abwehrmechanismus) sein.

- Auch wenn es Trost oder Schutz bietet, kann eine unkontrollierte Regression Beziehungen oder das tägliche Funktionieren beeinträchtigen.

- Erdungstechniken, Therapie und Selbstbewusstsein helfen Einzelpersonen, ihr emotionales Gleichgewicht wiederzuerlangen und Widerstandsfähigkeit aufzubauen.

Die Rückkehr eines Geistes in die Kindheit

Stellen Sie sich vor, Sie werden von Emotionen überwältigt—Ihr Körper spannt sich an, Ihre Stimme wird weicher und plötzlich fühlen Sie sich klein und suchen Sicherheit in Verhaltensweisen, die Sie einst als Kind beruhigt haben. Dieses Phänomen, bekannt als Altersregression, kommt häufiger vor, als den meisten bewusst ist.

Es geht nicht um Unreife; Vielmehr ist es die Art und Weise des Gehirns, Trost in einem vertrauten emotionalen Raum zu suchen, wenn sich heutiger Stress unüberschaubar anfühlt. Das Verständnis dieses psychologischen Musters kann Einzelpersonen dabei helfen, mit Mitgefühl statt mit Scham zu reagieren—und gesündere Wege zu finden, damit umzugehen.

Warum Altersregression wichtig ist

Das moderne Leben erfordert eine ständige emotionale Regulierung—am Arbeitsplatz, in Beziehungen und online. Wenn der Stresspegel seinen Höhepunkt erreicht oder alte Traumata wieder auftauchen, zieht sich der Geist als Schutzmechanismus manchmal in ein jüngeres geistiges Alter zurück.

Wenn dies nicht erkannt wird, kann es zu Verwirrung, Schuldgefühlen oder Beziehungsbelastungen kommen. Doch in Therapieumgebungen geführte Altersregression hat auch Potenzial als Instrument zur Wiederherstellung der Verbindung mit unterdrückten Emotionen oder ungelösten Kindheitserlebnissen gezeigt. Der Unterschied liegt in Kontrolle und Bewusstsein—ob Regression stattfindet zu Sie oder wird verwendet von dich.

Anzeichen und emotionale Auswirkungen

Eine Altersregression kann auf subtile oder ausgeprägte Weise auftreten. Zu den häufigsten Anzeichen gehören:

- In einem kindlichen Ton sprechen oder eine vereinfachte Sprache verwenden

- Suche nach Komfortobjekten (wie Stofftieren oder Decken)

- Vermeidung von Verantwortung oder Entscheidungen von Erwachsenen bei Stress

- Erhöhte Sensibilität für Ablehnung oder Kritik

Für manche bringen diese Verhaltensweisen vorübergehende Erleichterung. Wenn die Regression jedoch häufig oder störend wird, kann dies auf ein zugrunde liegendes Trauma oder chronische emotionale Belastung hinweisen. Studien zu Traumareaktionen zeigen, dass emotionale Regression oft mit Aktivierung des limbischen Systems—der Teil des Gehirns, der für Emotionen und Gedächtnis verantwortlich ist—, der rationales Denken bei Stress außer Kraft setzen kann [1].

Die Psychologie hinter der Regression

Sigmund Freud beschrieb die Regression erstmals als eine der geistigen Abwehrmechanismen, wo sich das Ego vorübergehend in ein früheres Entwicklungsstadium zurückzieht, um Konflikten oder Ängsten zu entkommen. Spätere Theorien der Entwicklungspsychologie, wie die von Anna Freud und modernen Traumaforschern, erweiterten diese Idee— und betrachteten Regression als Schutzreaktion wenn sich die emotionale Sicherheit bedroht fühlt [2][3].

Neurowissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse legen nahe, dass bei starkem emotionalen Stress die Amygdala (das emotionale Zentrum des Gehirns) aktiviert überlebensbasierte Reaktionen, während die präfrontalen Kortex, das das Denken und die Impulskontrolle steuert, reduziert vorübergehend die Aktivität [4]. Dieser Wandel kann zu Verhaltensweisen oder Gefühlen führen, die an die Kindheit erinnern—eine instinktive Rückkehr zur emotionalen Sicherheit.

Therapeutische Anwendungen und klinische Perspektiven

In der traumainformierten Therapie, kontrollierte Altersregression kann Teil eines Heilungsprozesses sein. Gesundheitsfachkräfte weisen Einzelpersonen manchmal an, frühere emotionale Zustände sicher noch einmal aufzugreifen Erinnerungen neu verarbeiten und neue Bewältigungsmechanismen entwickeln [5]. Im Gegensatz zur unwillkürlichen Regression —die dazu führen kann, dass man sich verloren oder desorientiert fühlt— erfolgt die therapeutische Regression in einem Strukturierte, sichere Umgebung wo der Einzelne Bewusstsein und Kontrolle behält.

Dieser Ansatz wird in Modalitäten wie verwendet Arbeit mit dem Inneren Kind und Hypnotherapie, zielt darauf ab, die emotionalen Bedürfnisse des “jüngeren Selbst” mit dem heutigen Bewusstsein zu integrieren und so emotionale Entspannung und Selbstmitgefühl zu fördern.

Gesunde Bewältigungs- und Erdungsstrategien

Wenn Sie eine unfreiwillige Regression erleben, gibt es wirksame Möglichkeiten, sanft in die Gegenwart zurückzukehren:

- Boden durch die Sinne. Konzentrieren Sie sich auf das, was Sie sehen, berühren oder hören können, um Ihren Geist im aktuellen Moment neu auszurichten.

- Verwenden Sie selbstberuhigende Techniken. Sanftes Atmen, das Einwickeln in eine Decke oder das Hören ruhiger Musik können den Komfort nachahmen, den Ihr jüngeres Ich sucht —ohne das Bewusstsein eines Erwachsenen zu verlieren.

- Tagebuch mit Mitgefühl. Schreiben Sie, als würden Sie freundlich zu Ihrem jüngeren Ich sprechen. Dies verbindet emotionales Verständnis zwischen Vergangenheit und Gegenwart.

- Suchen Sie eine traumainformierte Therapie auf. Ein qualifizierter Arzt kann Ihnen dabei helfen, die Wurzeln der Regression zu erforschen und Resilienzstrategien zu entwickeln, die auf Ihre Bedürfnisse zugeschnitten sind.

- Legen Sie sanfte Routinen fest. Vorhersehbarkeit fördert die Sicherheit und hilft Ihrem Nervensystem, sich nach emotionaler Überforderung zu stabilisieren [6].

Diese Praktiken beseitigen keine Regression, sondern helfen verwandeln in eine Chance zum Wachstum—eine emotionale Sprache, die, wenn sie verstanden wird, die Selbstverbindung vertiefen kann.

Nächste Schritte: Bewusstsein ohne Scham annehmen

Eine Altersregression zu erleben bedeutet nicht, dass du “kaputt bist.” Es spiegelt wider, wie sich der Geist unter Druck anpasst. Das Erkennen dieses Verhaltens ist der erste Schritt zur Heilung und emotionalen Regulierung.

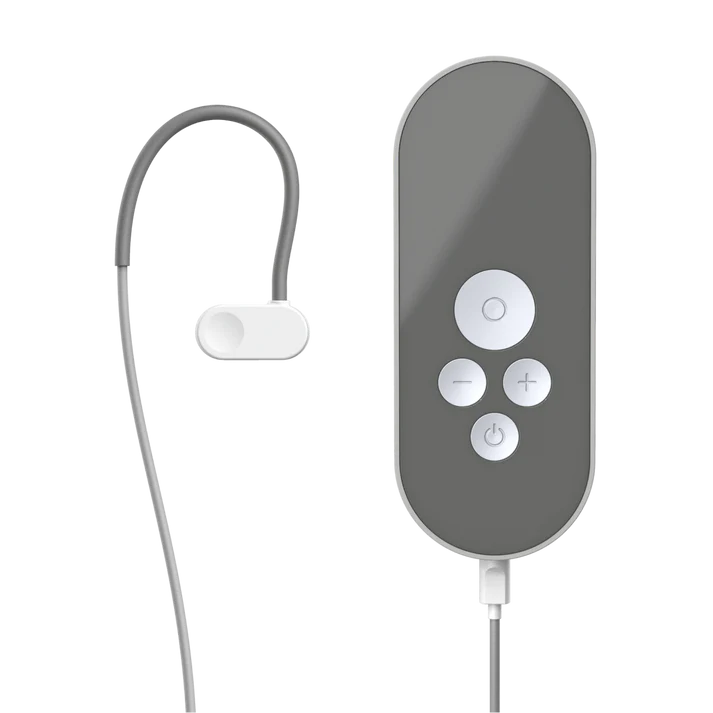

Für diejenigen, die unter Stress häufig Rückschritte machen, sollten Sie sich an einen wenden lizenzierter Therapeut, der in traumainformierten Ansätzen geschult ist. In einigen Fällen unter Einbeziehung tragbare Geräte die das Gleichgewicht des Nervensystems unterstützen —wie etwa CE-gekennzeichnete nicht-invasive vagale Neuromodulationssysteme—, können die Therapie ergänzen, indem sie die Emotionsregulation durch Stimulation des Vagusnervs sanft verbessern [7].

Schlussfolgerung

Die Altersregression bietet einen Einblick in die bemerkenswerte Fähigkeit des Geistes zur Selbsterhaltung. Ob durch Stress ausgelöst oder in der Therapie eingesetzt, es zeigt, wie tief unsere emotionale Vergangenheit unsere Gegenwart prägt.

Mit dem richtigen Bewusstsein und den richtigen Bewältigungsinstrumenten können Einzelpersonen Rückschritte von einer Quelle der Verwirrung in einen Katalysator für emotionales Wachstum verwandeln.

Der Artikel stellt in keiner Weise eine medizinische Beratung dar. Bitte konsultieren Sie einen zugelassenen Arzt, bevor Sie eine Behandlung beginnen. Diese Website kann Provisionen für die in diesem Artikel erwähnten Links oder Produkte erhalten.

Quellen

- Schore, A. N. (2022). Right Brain Affect Regulation and the Origin of Developmental Trauma. Frontiers in Psychology.

- Freud, S. (1936). The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense.

- Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence. Basic Books.

- LeDoux, J. (2014). Anxious: Using the Brain to Understand and Treat Fear and Anxiety. Viking.

- Malchiodi, C. (2015). Expressive Therapies and Trauma-Informed Care. Guilford Press.

- Siegel, D. J. (2018). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. Guilford Press.

- Clancy, J. A., et al. (2014). Non-Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Humans Reduces Sympathetic Nerve Activity. Hirnstimulation, 7(6), 871–877.