Puntos clave

- Depressive states in men often appear as irritability, anger, or overwork rather than sadness.

- Societal stigma and masculine norms contribute to underdiagnosis and delayed help-seeking.

- Biological and psychological differences influence how men experience emotional distress.

- Evidence-based strategies—like therapy, physical activity, and neuromodulation—can support recovery.

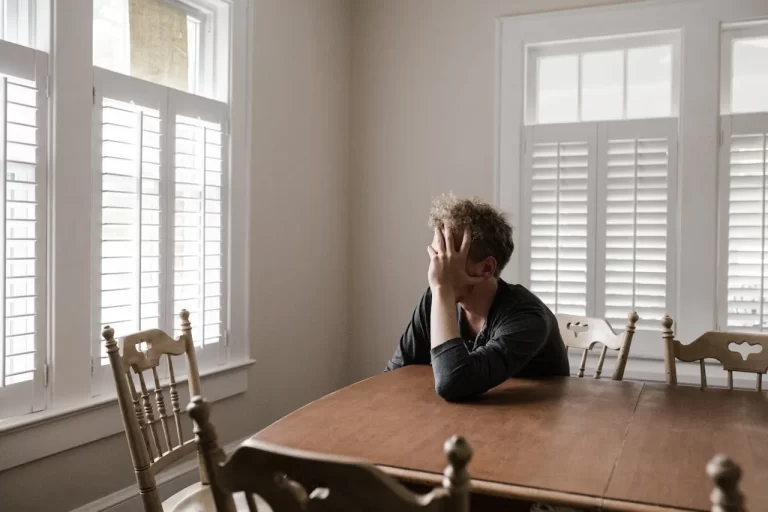

The Silent Struggle Behind a Stoic Face

Every day, approximately 130 men in the United States die by suicide—a tragic figure that underscores a silent crisis in men’s mental health [1]. Unlike popular portrayals of depression, many men experiencing depressive states don’t cry, withdraw quietly, or articulate feelings of sadness. Instead, they may appear angry, restless, or obsessively focused on work. Some turn to alcohol, risky behavior, or isolation as ways to cope.

These differences in how men express distress often make depressive states harder to recognize, both for loved ones and for the men themselves. “Men are socialized to be stoic,” notes Dr. Michael Addis, a psychologist who studies masculinity and mental health. “That conditioning can make emotional openness feel like a violation of identity rather than a path to healing” [2].

Why Early Recognition Matters More Than Ever

Ignoring depressive states in men can have devastating consequences. Research shows that men are less likely than women to be diagnosed with depression, yet they die by suicide at nearly four times the rate [3]. Untreated depressive states can lead to relationship strain, poor work performance, chronic tiredness, and even physical symptoms such as headaches, sleep problems, or heart palpitations.

Culturally, the problem is compounded by the expectation that men should “tough it out.” This mindset discourages vulnerability and help-seeking, allowing symptoms to persist or worsen. Recognizing the warning signs—before they escalate—is crucial for prevention and recovery.

Hidden Signs: When Distress Looks Like Anger or Exhaustion

While women often report emotional symptoms like sadness or crying spells, men’s depressive states can appear through changes in behavior, energy, or mood regulation. Common but overlooked signs include:

- Irritability or outbursts of anger

- Withdrawal from family or social circles

- Overworking or perfectionism as a coping mechanism

- Changes in sleep or appetite

- Substance use (alcohol, drugs, or stimulants)

- Loss of interest in hobbies or intimacy

- Physical discomforts such as fatigue, back pain, or digestive problems

According to the American Psychological Association, men’s emotional suppression often manifests as externalizing behaviors—aggression, impulsivity, or numbing—rather than the internal sadness more typical in women [4].

The Biology of Burnout: How the Male Brain Handles Emotional Load

The science of depressive states reveals important biological distinctions. Men and women differ in hormonal profiles, stress responses, and brain chemistry—all of which influence mood regulation. For example, testosterone levels can affect energy, motivation, and emotional reactivity [5]. Chronic stress also elevates cortisol, a hormone that, when persistently high, disrupts neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine involved in emotional balance [6].

Neurologically, depressive states alter activity in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala—regions responsible for decision-making and emotional processing. This can explain why some men experience blunted emotions, poor concentration, or quick tempers. Inflammation has also emerged as a biological factor; elevated inflammatory markers have been linked to mood changes and fatigue [7].

Understanding these mechanisms helps reframe depressive states as a whole-body experience, not a weakness of will.

Turning Awareness Into Action: Practical Ways to Rebalance Mood

While every person’s experience is unique, evidence-based strategies can significantly support mental wellness in men.

- Talk Therapy and Connection

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy have been shown to reduce symptoms and improve emotional regulation [8]. For many men, starting with a structured, goal-oriented format makes therapy feel more approachable. - Physical Activity as Medicine

Regular movement—whether through walking, resistance training, or sports—has measurable antidepressant effects, improving both mood and sleep quality [9]. - Mindfulness and Stress Reduction

Techniques such as meditation, deep breathing, or journaling help manage anxious thoughts and reduce physiological stress. - Healthy Habits and Nutrition

Prioritizing balanced meals, consistent sleep, and limited alcohol use supports neurotransmitter function and overall well-being. - Exploring Innovative Solutions

Emerging technologies like CE-marked non-invasive vagal neuromodulation systems offer new ways to regulate mood through gentle stimulation of the vagus nerve. Early studies suggest good tolerability and potential benefits for mood-related outcomes; most reported side effects are mild and transient. - Knowing When to Reach Out

Persistent symptoms lasting more than two weeks, loss of interest in usual activities, or thoughts of self-harm warrant immediate attention from a health professional or helpline.

Changing the Conversation Around Men’s Emotions

Recognizing depressive states in men starts with empathy and awareness. Asking a friend, “How are you—really?” or sharing one’s own struggles can open doors to meaningful dialogue. The more openly men talk about emotional challenges, the more likely they are to find effective support.

Depressive states are not a reflection of strength or weakness—they are a human response to stress, loss, and imbalance. Early recognition and intervention can restore energy, clarity, and connection.

Conclusion: Courage Begins with a Conversation

Men’s mental health deserves the same visibility and compassion afforded to any physical symptom. Understanding that depressive states can appear in unexpected ways is the first step toward change—one conversation, one check-in, one small act of courage at a time.

If you or someone you know may be struggling, reach out to a trusted health professional or contact the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline in the U.S.

El artículo no constituye en modo alguno un consejo médico. Consulte con un profesional médico autorizado antes de iniciar cualquier tratamiento. Este sitio web puede recibir comisiones por los enlaces o productos mencionados en este artículo.

Suscríbase gratis para obtener artículos de salud más perspicaces adaptados a sus necesidades.

Fuentes

- CDC. (2023). Suicide Data and Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/

- Addis, M. E. (2008). Gender and Depression in Men. Clinical Psychology Review.

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2024). Men and Depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov

- American Psychological Association. (2022). Depression in Men: Understanding the Signs.

- Zarrouf, F. A., et al. (2009). Testosterone and Depression: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Practice.

- McEwen, B. S. (2017). Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation. Physiology & Behavior.

- Miller, A. H., et al. (2009). Inflammation and Its Discontents: The Role of Cytokines in Depression. Biological Psychiatry.

- Cuijpers, P., et al. (2016). The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. World Psychiatry.

- Schuch, F. B., et al. (2018). Exercise as a Treatment for Depression: Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research.

- Clancy, J. A., et al. (2021). Non-invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation and Emotional Regulation. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

- Call, J. B., & Shafer, K. (2018). Gendered manifestations of depression and help seeking among men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315623993

- Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Reijnders, M., & Huibers, M. J. H. (2016). How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry, 15(3), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20346

- Driessen, E., Hollon, S. D., Bockting, C. L. H., Cuijpers, P., & Turner, E. H. (2015). Does publication bias inflate the reported efficacy of psychotherapy for major depressive disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(5), 444–455. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070899

- McEwen, B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006

- Miller, A. H., Maletic, V., & Raison, C. L. (2009). Inflammation and its discontents: The role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 65(9), 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029

- Schuch, F. B., Vancampfort, D., Richards, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023

- Staiger, T., Waldmann, T., Rüsch, N., & Krumm, S. (2020). Masculinity and help-seeking among men with depression: A qualitative study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 599039. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.599039

- Zarrouf, F. A., Artz, S., Griffith, J., Sirbu, C., & Kommor, M. (2009). Testosterone and depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 15(4), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000358315.88931.fc

- De Smet, S., et al. (2021). Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation enhances cognitive emotion regulation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 145, 103933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103933

- Ferstl, M., et al. (2024). Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation conditions increased invigoration and wanting in depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 132, 152488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2024.152488